Kerala Vision 2047 must place the state’s great rivers—Bharatapuzha, Pamba, and Periyar—at the centre of its ecological, economic, and cultural future. These rivers are not simply water channels; they are civilisational arteries that shaped Kerala’s identity, agriculture, rituals, migration patterns, biodiversity, and knowledge traditions. Yet, despite their historic and cultural significance, modern Kerala has not fully utilised these rivers as engines of ecological innovation, economic opportunity, or global learning. By 2047, Kerala must position its rivers as living laboratories of sustainable development and as symbols of a state that respects nature while building prosperity.

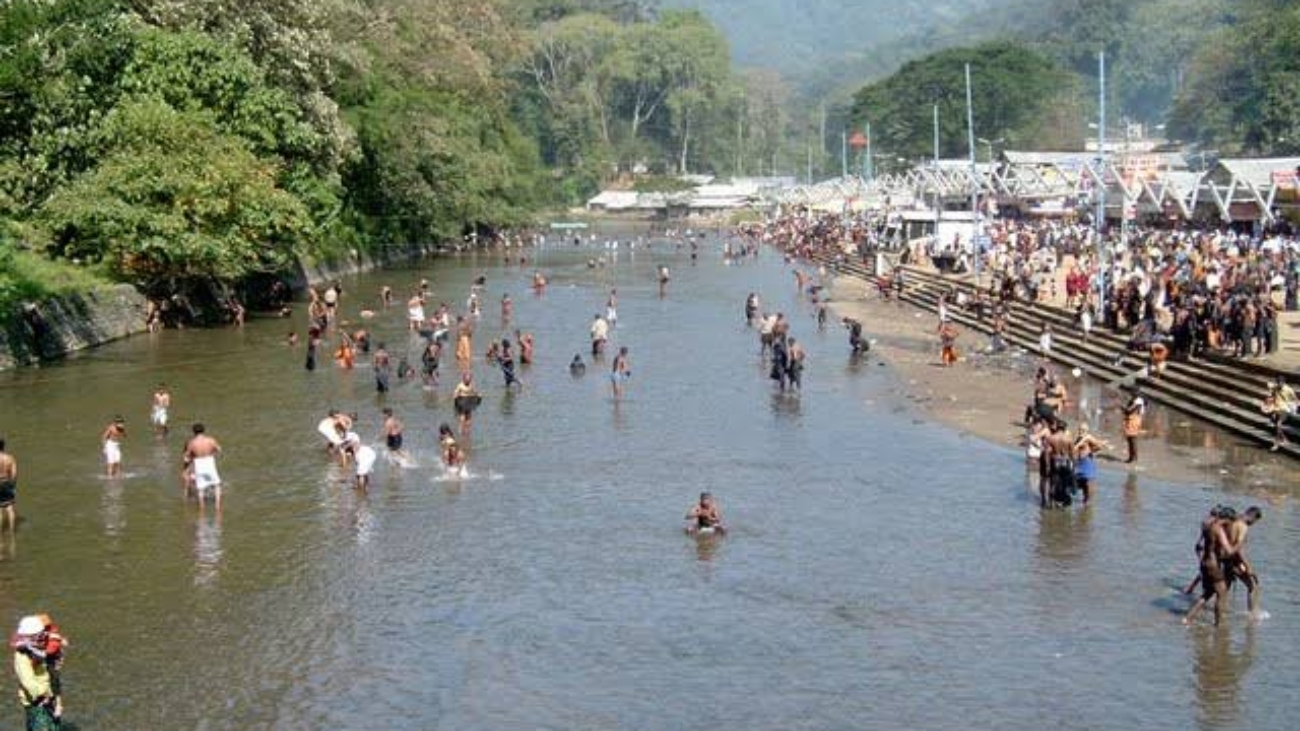

Bharatapuzha, the river of poets and performers, flows through a landscape that nurtured Kerala’s classical traditions, from Nila-based literary movements to rural craftsmanship. Pamba, the river of pilgrimage, sustains forest ecosystems, indigenous communities, and the cultural power of Sabarimala. Periyar, Kerala’s lifeline, energises industries, agriculture, drinking water supply, and hydropower systems across districts. Together, these rivers form a triad of ecological strength and cultural continuity. Yet all three face severe pressures—sand mining, encroachment, pollution, water scarcity, industrial effluents, and altered flow patterns caused by climate change. Vision 2047 must reverse this decline while creatively unlocking their economic and ecological potential for global leadership.

The first step is placing Kerala’s rivers at the centre of climate adaptation. As rainfall becomes more erratic and drought–flood cycles intensify, rivers must be treated as dynamic climate buffers. Bharatapuzha needs watershed restoration to revive its base flow during summers. Pamba requires forest catchment protection to stabilise monsoon recharge. Periyar’s flow dynamics must be managed scientifically to balance hydropower, irrigation, drinking water, and ecological needs. River rejuvenation cannot be a cosmetic project; it must involve soil regeneration, riparian vegetation, aquifer recharge, and strict enforcement against illegal extraction. By 2047, Kerala can present a scientifically restored river system that becomes a global model for tropical river resilience.

Kerala’s rivers also carry immense economic potential, particularly in the emerging green economy. Bharatapuzha’s vast riverbed areas can host controlled sand regeneration studies, eco-tourism trails, and cultural festivals that bring economic benefits without environmental harm. Pamba’s unique ecology allows for premium forest-based products, medicinal plant cultivation, and tribal entrepreneurship. Periyar can serve as a centre for advanced freshwater aquaculture, river-based logistics, and environmental research hubs. River economies must be redesigned not around extraction but renewal, creativity, and knowledge export.

Another major opportunity lies in freshwater-based tourism and cultural branding. Bharatapuzha can be developed as a cultural corridor that celebrates music, poetry, folklore, martial arts, and craftsmanship. Pamba can host curated pilgrim ecology experiences where travellers understand forest rituals, riverine ecology, and the cultural symbolism of water. Periyar can integrate scientific tourism by offering guided experiences on hydrology, wildlife, dam engineering, and riverine biodiversity. These rivers are cultural assets that can attract global travellers seeking depth, authenticity, and ecological learning rather than mere sightseeing.

Kerala’s rivers also hold powerful lessons in biodiversity. Bharatapuzha’s dry-season habitats support unique plant species, birds, and riverbed organisms that survive extreme seasonal shifts. Pamba sustains freshwater fish diversity, forest wildlife, and migratory bird pathways. Periyar, with its connection to the Periyar Tiger Reserve, anchors one of India’s most complex ecological networks. By 2047, Kerala must map these ecosystems scientifically and develop river-based biodiversity laboratories, freshwater research centres, and collaborations with global universities. Knowledge generated from these rivers can guide conservation policies across tropical regions worldwide.

A transformative opportunity lies in integrating rivers with digital and scientific innovation. Kerala can deploy real-time water quality sensors along the rivers, satellite monitoring of riparian zones, AI-based flood prediction tools, and GIS-based river health dashboards. These technologies can protect rivers from pollutants, illegal encroachment, and climate disasters. By 2047, Bharatapuzha, Pamba, and Periyar can become the most scientifically monitored rivers in tropical Asia, setting new benchmarks for data-driven ecological management.

Economically, river-based industries can be redesigned for sustainability. Bharatapuzha’s sand-based economy can evolve into eco-material research, producing engineered river-sand alternatives. Pamba’s cultural tourism can expand into premium agri-produce, herbal pathways, and forest-to-market value chains that uplift tribal communities. Periyar’s water-based industries—including fisheries, drinking water supply, agriculture, and river transport—can be modernised with better technology, safety systems, and global certifications. Kerala’s rivers can become centres of livelihood diversification rather than overuse.

A deeper cultural mission must also guide Vision 2047. Kerala’s rivers are custodians of memory, ritual, pilgrimage, and artistic identity. Bharatapuzha nurtured countless writers and performers, shaping the intellectual fabric of the region. Pamba is inseparable from the spiritual journeys of millions and from the oral histories of tribal communities. Periyar carries stories of agricultural transformation, community life, and industrial development. Vision 2047 must amplify these cultural narratives through museums, festivals, riverfront cultural centres, and documentary creation. If Kerala positions its rivers as cultural icons, they will gain global recognition similar to how Japan celebrates the Kamo River or how France elevates the Loire.

Urban and rural development must also integrate river wisdom. Cities built near these rivers—Shoranur, Cheruthuruthy, Pathanamthitta, Aranmula, Chengannur, Aluva, and Ernakulam—must design riverfronts that prioritise wetlands, green zones, walking paths, cultural spaces, and eco-friendly public amenities. By 2047, Kerala can create river-centric urban design models that the world can study. Instead of concretising riverbanks, Kerala must allow space for seasonal floods, natural recharge, and biodiversity migration.

The rivers also provide avenues for education and youth engagement. Kerala can develop river schools where students learn hydrology, ecology, oral histories, and traditional knowledge. These schools can train the next generation of conservationists and policymakers. Youth kayaking clubs, river cleanup networks, biodiversity monitoring groups, and climate volunteer teams can transform rivers into spaces of civic responsibility.

By 2047, Kerala must treat Bharatapuzha, Pamba, and Periyar not as resources to be used but as systems to be understood, celebrated, and protected. The rivers must become symbols of knowledge, identity, resilience, and economic innovation. A state that honours its rivers also honours its future.

If Kerala embraces this vision, its rivers will no longer be sites of degradation or crisis. They will become international examples of how ecological intelligence, cultural pride, and economic strategy can flow together to create a new model of prosperity. The rivers that shaped Kerala’s past can, if reimagined wisely, shape its global future.